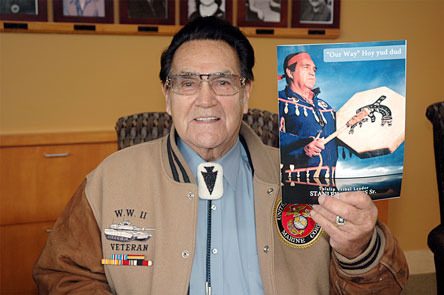

TULALIP — At 83 years of age, Stanley Jones Sr. has led a life so full that it could fill a book, and it already has.

After 44 years and 15 consecutive elected terms of service, Jones is stepping down from the Tulalip Tribal Board of Directors April 3, and on April 11 and 12 from 11 a.m. to 1 p.m. at the Tulalip Resort Casino Gift Shop, he’ll be signing copies of his book, “‘Our Way’ Hoy yud dud,” a history of both his own life and the Tulalip Tribes as a whole.

“I thought for a long time that I didn’t know anything about writing a book, but I’ve been writing down things for years, so I thought, well, shoot, maybe I could make a book out of everything I’ve already written down,” Jones said.

Jones has accumulated a wealth of experiences over several decades, from serving in the Marine Corps during World War II and feeding his rations to Hiroshima survivors, to greeting such distinguished dignitaries as Bill Gates, the Rev. Jesse Jackson, Nelson Rockefeller, Donald Trump, Chinese President Hu Jintao, and U.S. presidents Bill Clinton and George W. Bush. He’s spoken on Native American issues at the invitation of the United Nations in Geneva, Switzerland, regarding treaty and environmental issues, and in China and Italy regarding economic development, and his cultural exchange work has also taken him to Goa, India, and New Zealand.

For all these travels and meetings with luminaries, what Jones recalls most vividly are the tough times that the Tribes faced during his early life and previous years on the Board.

“When I was a kid, we got our flour from the government commissary, and they gave us sifters because it had worms,” Jones said. “People were starving on the reservation. There was no electricity. We had to use kerosene lamps for light and a milk can to fetch water. There was tuberculosis all over. My mom died when I was 3, and my brother and I got sent to Cushman Indian Hospital in Tacoma when I was 9. He passed away there, and I didn’t leave until I was 12.”

Jones recalled how Native American children were placed in government schools, away from their families, and denied the ability to learn their cultural heritage. For this reason, he devoted several pages of his book to photographs and biographies of past and present Tribal members, passages about Tribal treaties and customs, and definitions of Native American names and words.

“I don’t want these things to be forgotten,” Jones said. “It used to be that they took the language away from the young people, and punished them for speaking it, but now, it’s taught to them in the schools.”

Jones always enjoys pointing out that the Tribal government only maintained three full-time employees when he began his first term on the Board in 1966, whereas now, they employ more than 4,500. He laughed as he admitted that he never imagined such growth was possible when he was younger, and he attributed it to the Tribes gradually building “a little bit at a time.” His tenure on the Board has been marked by his concerns with preserving Native American rights and stimulating the Tribes’ economic development.

Jones has also served as president of Quil Ceda Village and on the Tribes’ Gaming Hunting, Fishing and Business committees. He was also appointed as first chair of the Task Force on Indian Gaming, and negotiated for the first tribal/state casino gaming compact. He helped revive the Tribal Salmon Ceremony in 1976, and was instrumental in forging the Boldt Fishing Treaty Decision, which ensured tribes would receive their treaty rights of half of all harvestable salmon in the state.

A great-great-grandfather several times over, Jones isn’t entirely sure how he and his wife of 60 years, JoAnn, will spend their time, but the Board is so sure that he’ll continue to counsel Tribal leadership that they’ve installed a permanent seat with his name on it in the Board room.