TULALIP — The mothers who attended the Feb. 17 community meeting on suicide prevention and teen issues at the Tulalip administration building had been touched by tragedy.

Amy Sheldon’s daughter has found it difficult to return to Marysville-Pilchuck High School in the wake of last fall’s shooting.

“She still can’t walk by the cafeteria,” Sheldon said.

Bonnie Juneau’s two children, both M-PHS students, have found it harder to express their feelings.

“My oldest acts cool, like nothing’s wrong,” Juneau said. “My youngest is going into isolation.”

Juneau turned down a request by her younger child to have a cable run into their bedroom.

“I said, ‘No, you need to interact with others,'” Juneau said. “They don’t process this tragedy the same way.”

Completely unrelated to the shooting, Rose Iukes’ daughter committed suicide last year, leaving her to raise her granddaughter, while her son survived a recent suicide attempt.

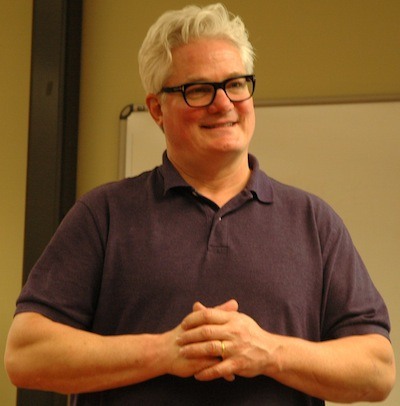

Dr. Robert Macy, president of the International Trauma Center, went one further, by identifying differences in how boys and girls react.

“Boys tend to disassociate, while girls get in your face,” Macy said. “You need to talk to your teens about what’s meaningful to them, even if you may not like what you hear.”

Macy is part of a team of experts that has been working in the community to help it heal after the deaths of five students four months ago.

Iukes asked how a parent should strike a balance between fostering a sense of trust with one’s suicidal child, versus “checking the kitchen to make sure they haven’t taken any knives.”

Juneau suggested that the community shoulders some of the blame for suicidal teens’ behavior, by paying more attention to tragic deaths than they do on celebrating life.

“There have been so many tragedies, one right after the other, that our kids have become numb to it,” Juneau said. “No wonder they seem to be rushing to die.”

Iukes added, “We have to listen to our kids.”

Sheldon, president of the Marysville Special Education PTSA, suggested volunteering at schools for parents who are able.

“Sitting at the lunch tables with these kids, I can spot things that teachers don’t always see,” Sheldon said.

Donna Amundson, of the Sources of Strength Peer Leader Program, outlined eight sources of strength that teens and their parents can draw on, including family support, positive friends, mentors, healthy activities, generosity, spirituality, medical access and mental health.

“None of us have all eight of those things,” Macy said, but you can recognize your strengths and use them to compensate for your shortfalls.

Tulalip Police Chief Carlos Echevarria admitted that tribal leadership was exhausted following the shooting.

“Right before the holidays, we were just looking forward to the tribes shutting down for a while,” Echevarria said. “Our mental health was fragmented.”

Macy noted that this can create a feedback loop, where kids want to safeguard the adults’ emotional well-being by not sharing certain details.

“They want to take care of you, too, and that’s how things can get frozen,” Macy said.

Macy acknowledged that teens can be prone to hyperbolic statements about their own well-being, especially online, which is why he urged parents to check whether their children are thinking of hurting themselves, or if they see pain as the only solution.

“You can inject hope into the discussion simply by pointing out that these problems are treatable,” Amundson said.